Tobias Wolff in his Memoir, ‘This Boy’s Life’ written in the 1950s is the story of Toby [Tobias Wolf] who flees to Washington with his divorced mother Rosemary who courageously breaks free from a cheerless marriage with Roy. Desperate for a safe haven for her son, a stable provider, the normalcy of a family and a father-figure for Toby, she compromises on living with a presumably even-tempered man she remarries, Dwight. Though Rosemary soon recognizes him as a man who uses aggression to discipline his stepson, she remains unforgivably silent to the abusive husband. She struggles to maintain hope in the dismal circumstances, for the permanence of a relationship, even if that meant finding a make-believe-happy medium in a compromising relationship with someone like Dwight.

Wolff has remarkably put in writing his experiences which were turbulent, emotionally chaotic and with sprints of prejudices. However, he delivers a story without arousing hostility in the reader’s mind by ‘normalizing the incredible’. It was a tight rope walk for the author to get the readers to go along with his sentiments. A Memoir is written more out of experience than imagination, yet he refrained from an over-personalized narration. Wolff did not seem to be leading the reader to empathize with him through excessive accentuation of the high and low points along the storyline.

In a recent book review, I wrote, I couldn’t help admit in a close, “The book loses me when my mind squanders off from reading the story to reading the author’s mind.” In Wolff’s Memoir, I tried to meander around Toby’s thoughts and perceptions on how he related to the gloominess that only seemed to grow thicker with the introduction of Dwight’s forbearing character. Each time I sensed moments when his pent-up twinges would spark over, he averts the ‘incredible’ from flaring up the literary plot.

The book gives lucid insights into the dilemmas and miseries of a single mother and a young boy in a struggling boyhood. Conspicuous to the story is Wolff’s narration of slackening and intensification of courage. Despite Dwight’s sadistic trips at domineering Toby, Wolff underplays the trauma when asked for his opinion before Rosemary consented to Dwight’s proposal-a subtle depiction of Rosemary sacrificing for Toby and Toby sacrificing for Rosemary in the face of offensive bearings. While he puts forth a case for the psychological crunches he endured, Wolff also tends to the intersubjectivity by cataloging Dwight’s disposition along with the plot, allowing readers the prerogative to interpret the projection of Dwight’s character, as perhaps, a perverse exercise of ‘mending Toby.’

And the one I particularly liked was where Toby lets in on Dwight’s repugnance for him as he writes, “He thought I was growing out of malice” [implying growing tall, thus needing new clothes], giving the reader a perspective on his evaluation of Dwight’s personal conflicts, recounted by him with an amazing journalistic objectivity.

He presents to the readers Toby’s boyish quirks at springing up a pipe-dream escape, prospecting liberty and a brand-new identity for himself. With Paris in sight, his exhilaration at possibly breaking away from a life with a control freak Dwight and exercising his power of choice has been skillfully narrated.

The last few scenes were set in within ‘hope’ and ‘anti-hope’ with Toby’s callowness at comprehending what meant more- a life away from Dwight without Rosemary; or a life with Rosemary despite Dwight. And his call at choosing who he was with his mother [undeterred by the deprivation, intimidation, and vengeance of allowing existence with Dwight] over who he could become past Rosemary was very sensitively portrayed.

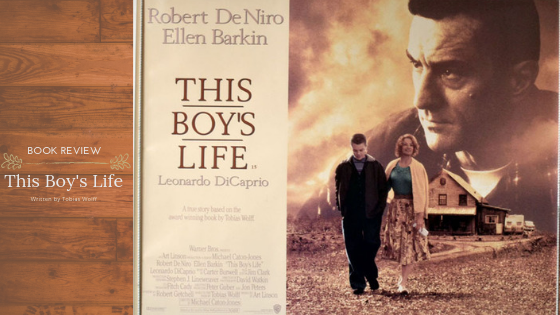

The book is a memoir of writer and literature Professor Tobias Wolff, that was later adapted into an award-winning movie ‘This Boy’s Life’ starring Robert De Niro and the then-young Leonardo DiCaprio